Interview with Kode9, via e-mail, late September 2006.

Kode9 + the Spaceape live in Berlin, 09/15/06

Where and when have you and Spaceape met each other and eventually decided to work together?

We met in 2009 in South London via a mutual friend. Our first track together ‚Sine of the Dub‘ was an accident. Spaceape dug out one of his favourite tunes, Prince’s ‚Sign of the Times‘ and read the lyrics off the back of the album, changing the odd word, and I built a quick bass pulse with some fx. That was that. It didn’t take long.

How did the album „Memories of the Future“ come about and did you start working on the album with a certain concept in mind?

We’re just trying to keep ourselves interested, thats all. We’ve just been tweaking our sound since the label started, working from the bottom up and gradually adding colour. There was no real concept in mind for us. Its always a bit random, and its the tone of Spaceape’s voice that tends to form the consistent thread through the tracks rather than some overarching sonic concept. We make quite a range of tunes, some without beats, some with, so in a way doing an album is a good format for us.

Kode9 + the Spaceape in Berlin

Some writers describe dubstep as being distinctively influenced by and closely connected to its place of origin (i.e. London). Would you say that your music is influenced by your physical and cultural surroundings as well – and if so, how?

While a lot of what has been said about grime and dubstep being influenced by its place of origin is real, i think that it can also become a tedious cliche which says as much about the poverty of imagination of journalists and producers as it does the relationship of certain music to their urban environment. We’re not really interested in music that merely reflects an urban environment. I don’t think any music simply does this. The minute you make a noise you’re changing your environment. So for us its more about transforming your environment than reflecting it – bringing out that which is alien in your environment. We are influenced by the quantum diaspora.

Kode9 + the Spaceape still in Berlin

Futuristic ideas – both utopian and dystopian – have been an important aspect of electronic music since its beginnings. „Memories of the Future“ draws a rather dystopian and dark image of the „future“ which already „infects the real present“ (as the press release states). Where does this uneasiness come from?

The uneasiness comes from the nervous state of the world. Reality has collided with science fiction. The future has collapsed in on the present. For us, thats what the feeling of dread in our music is about, the ominous anticipation of the future in the present.

Could you explain what Spaceape means by „audio-fiction“?

The concept of sonic fiction was invented by Kodwo Eshun in his book „More Brilliant than the Sun“. He describes it as „frequencies fictionalized, synthesized and organized into escape routes. . .“ through „real-world environments that are already alien“ „Sonic fiction, phono-fictions generate a landscape extending out into possibility space. . . an engine. . .[to] people the world with audio hallucinations.“

In terms of music, the past is present on the the album to a similar extent as the future, as there are lots of traces and samples of different genres. Could that mean that the „memories of the future“ are somehow „echoes of the past“?

We’re more interested in the way that what is happening in the present is both an echo of events that have happened in the past, and an echo of events that are yet to come, events in the future. Thats the kind of temporality we are interested, time scrambling, time loops which lay outside of chronology. The co-existence of the future and the past in the present. Thats why films like Chris Marker’s „La Jetée“ are so powerful and influential. We’re also interested in how futurisms pass like fashions. Our album cover image, its ambiguous building/spaceship thing, is now like an old fashion vision of the future, it kind of looks old fashioned. Each period has its own retro-futurism in visual and music culture. The future is not what it used to be.

„Memories of the Future“ has been released on Hyperdub Recordings.

For more words and thoughts from the Kode head over to the Red Bull Music Academy for an entertaining video lecture (part 1, part 2) or visit „Fact Magazine“ for an interview by Mr. K-Punk.

Parts of this interview have been used for a feature article on Kode9 + the Spaceape in the current issue of „Groove“ magazine.

November 1st, 2006

Two weeks before I did this interview on the phone, I had been visiting the now almost legendary DMZ rave at Mass in Brixton, South London (check my photos here). DMZ has become the central night for the dubstep scene, if not even a kind of its spiritual centre. As it’s taking place in the back part of a church in which front part actual services are still held, you might think DMZ’s slogan „Come and meditate on bass weight“ is just a cheap promotional joke. But the dedicated vibe of the crowd, the way it enthusiasticly celebrates the music, swaying in unison with the waves of bass, really resembles a bit of a spiritual congregation.

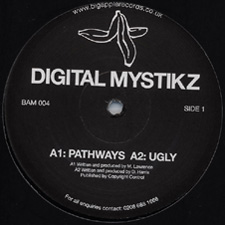

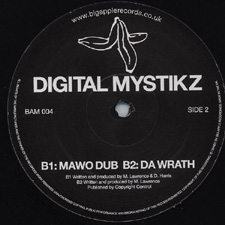

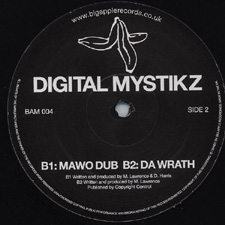

One of the promoters of the night is Mala, who is also one half of the production outfit Digital Mystikz and part of the DMZ label team. DMZ are not only responsible for the most important rave of the scene, but have also been very influential on the sound aesthetic and the musical evolution of dubstep since their first release about three years ago. So here’s Mala in his own words on his musical influences, sound systems, spirituality and much more….

Mala @ DMZ, May 2006

Where in London are you from originally?

I’ve grown up in Norwood, SE 25, South London.

How did you get into making music?

It was something I naturally progressed into. I have always been listening to music, but it was about 1992 when I heard jungle music on the pirate radio stations that I thought about making music myself for the first time. I was really taken by hardcore jungle and I started doing music in my head every day. It all stems from there, really! Then I started writing music probably about 2000 or 2001 and began taking it seriously about a year later than that.

So hardcore and jungle are your main musical influences then?

Not really, no. I don’t think I could say that they are the main musical influences in what I do now. I think the influences stem from all aspects of life, not just from music. There’s been so much music that’s influenced me over the years, so many different styles, so many different artists, different sounds and instruments, environmental sounds – everything, man! So, it’s just a mash-up of styles all the way from jungle to dub to jazzy stuff to world music. I can’t say that one particular musical style has influenced me more than another.

But maybe saying that, it was jungle music I listened to, which I scrutinized every little bit of, every beat, for years and years and years. So maybe the foundation of what I do is jungle. Nevertheless, all the tracks I do are just different. I enjoy experimenting with sounds. I always like to start off with new drum sounds and new samples when I’m doing a new beat. It just keeps things fresh for me that way, because at the end of the day it’s about enjoying writing music, its not about anything else!

In my opinion, it’s this variety of sound that makes your music really interesting, because you’ll never know what the next DMZ track might sound like…

I’m lucky that you’re actually talking about DMZ! Coki’s got his side to what he does and Loefah’s got his own take on everything as well, so it’s a mash-up of a lot of different sounds.

Just to set the record straight: You and Coki are Digital Mystikz, but there are more people involved in DMZ (the label and parties), e.g. Loefah…

That’s right. Loefah has always produced as Loefah, and myself and Coki, we have always produced as Digital Mystikz. We have known each other for years and years and years…

from left to right: Mala, Coki, Loefah @ DMZ, May 2006

We started the label because we wanted to represent ourselves, we wanted not to be misrepresented. At that time there wasn’t really going on much else. There were a few labels like Big Apple and Tempa, but nobody really knew how to call the music, everybody was calling it something different. So we thought we should call it the DMZ sound, so people could understand where it was coming from.

Tell us a bit about how a Digital Mystikz track comes into existence: Are you and Coki always working together, or is it sometimes your tune and sometimes one by Coki? It’s not always mentioned on the record labels…

It varies: Some tracks we do together, some tracks we don’t. A lot of the time we work on stuff individually. None of that is the result of premeditated decisions, it’s just a matter of time and circumstances. And things are different in our lives now than they were when we started!

It was around 2002 when we both decided that we wanted to take writing music a little bit more seriously. We didn’t take this decision because we were thinking of selling records or anything like that. We wanted to write music just for us, for nobody else. It just happened that we played some stuff to Hatcha and he was like: “Ah, I could play some of this shit!” The next thing we knew was that Hatcha was playing some of our tunes. Six month after that, it must have been in June 2003, he played “Pathways” for the first time at Plastic People.

The impact was shocking, to be honest! From my point of view, as somebody who made it, I didn’t expect people to respond to the music in that kind of way. But that got things moving: Before that it had been just us making music for ourselves, and all of a sudden there was a platform for what were doing. At the same time, people started to call our music “dubstep”. I never actually said that I write “dubstep”…

But do you actually like the term “dubstep”?

If it wasn’t “dubstep”, it would be called something else. It seems like there is a need for a name in order to sell the music: Labels and magazines want to have a name for it, the shops want to have something to put on their shelves.

For me it’s a personal thing: People might hear certain things in the sound that remind them of the music they regularly listen to and they relate it to that. Some of the people say: “Oh, it sounds similar to this or that, some of it sounds like techno, some of it sounds like house, some of it sounds like drum’n’bass.”

At raves Digital Mystikz usually play out as a sound system (with you and Loefah on the decks and Pokes on the microphone). The set up and the way you play reminds me of a traditional reggae sound system. Do you see yourself in that tradition?

Actually, I’ve always grown up around that. If I go back to listening to jungle music, you had a DJ and a mic man. The DJ would play dubplates and the MC would host. I’m talking about MCs like Moose and Five O who used to spit lyrics as well, but they weren’t like Shabba or Skibadee, they were different. It’s kind of a similar thing to a dub/reggae soundsystem, but for me that’s normal, that’s not really following any particular tradition. I’ve always seen music being played this way – apart from bands and stuff, which is obviously a totally different thing – but from a DJ’s point-of-view that was just how it was done!

DMZ, May 2006: Sgt. Pokes, Spaceape, Kode 9 (from left)

It wasn’t like: “Alright, let’s have a DMZ soundsystem!” I never used to DJ until I was asked to play at a party. I thought, well, they’ve asked Digital Mystikz to play, so I might as well do that and just play all my music. And that’s really how it came about. Loefah already used to DJ years ago and Pokes had always MC-ed. So it was just natural. It’s kind of weird, cause everything we do now is almost like it’s an extension of our bedroom when we was teenagers. We always used to do jam sessions – me, Coki, Loefah and Pokes. It’s just nice to be able to go out and share positive experiences and push out positive vibes to people.

What are your feelings about things having grown to such an extent right now?

I’m shocked! There’s no way to really describe it. I’m very grateful for everything that’s going on at the moment, but if you want to sum up how I feel in one word: I’m shocked! None of us had planned this, so it’s really enjoyable to hear what people have been saying about the music and it’s nice to go out and about, put out music and just create something positive for people.

So there are no downsides of the whole thing to you?

M: I suppose, if you want me to look at life, there are always downsides like there’s also positive stuff. But in terms of like music there’s no downside to it at all. In terms of business – that’s boring: I like music, I like writing music, but I don’t like doing accounts. If there is a downside to it it’s the business side of it.

There are a lot of references to spirituality in the world of DMZ – just think about the subtitle of the DMZ rave („Come meditate on bass weight“) for example. Are you a spiritual person? Is it something you’re really into?

I think it’s part of everything in life. Whether people choose to see certain things or not comes down to the individual. And that’s another reason why I won’t describe my sound – as you have asked me before in your email. For me it’s not about how I perceive my sound, it’s about how you or the person next to you receives it. I don’t really feel comfortable describing it, because how it hits me and you might be in a totally different way. I would like to have it left undescribed.

Coming back to the spirituality question: To me writing music is like a form of meditating, it’s a way that I’m able to release certain things from inside out – whether you had a good day or a bad day or something is troubling you. That’s why I write music. It’s almost as necessary for me as water, it’s something I have to do. I don’t have to write music and put music out in a shop for people to buy it, that’s not what I need. I just need to write music. People buying it and people enjoying it – I give thanks for that!

I suppose I could go further into the spirituality thing, but I think people should take what they want from the music. If people – whatever they may believe in or not believe in – feel about it in a certain way – as long as it’s positive, that’s what it’s about for me! That’s why I say meditate, because when it comes to our dance, that’s what I want people to do. I want it to be a positive meditation. I’m not into no madness, man!

Obviously, in the music itself you have certain dark sounds. They are not dark in the sense of “evil” or “menacing”, but they are serious. I think that’s where you find the meditation, because – although it’s obviously designed for a big sound system, it’s one of the types of music you can listen to on different levels. But I think you can take it or leave it.

The latest release on the DMZ label (Loefah: „Mud/Ruffage“ (DMZ 009)) has just left the pressing plant and should be available in good record shops worldwide.

Quotes from this interview have been used for a three-page background feature on the dubstep scene which I wrote for Groove magazine. The issue should be available until late August on newsstands throughout Germany.

Juli 24th, 2006